![OIP[6]](https://bokamosoyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/OIP6.jpg)

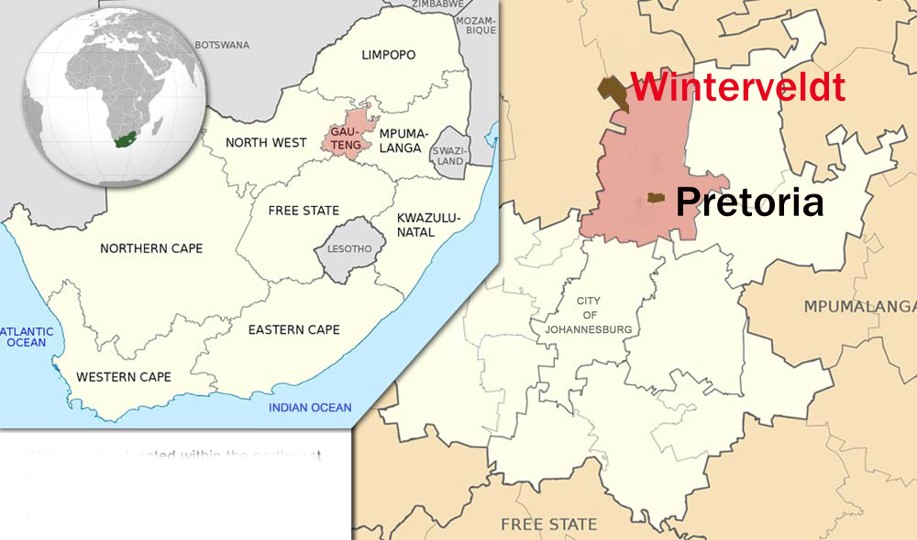

Winterveldt

Winterveldt is a settlement situated in Gauteng Province, about 35 miles northwest of Pretoria, the administrative capital of South Africa. It is adjacent to the black townships of Mabopane and Soshanguve and is approximately 40 square miles in area with a population of 120,800. Major language groups include Tsonga 22 percent, Tswana 20 percent, Zulu 19 percent and Pedi 13 percent although all of South Africa’s eleven official languages are spoken in Winterveldt.

Prior to colonization, the area was farmland occupied by African tribes. The land was taken over by white settlers and used as a grazing ground for livestock during the dry winter seasons, hence the name Winterveldt, meaning “winter field”. Between 1938 and 1945, the area surrounding Winterveldt was incorporated into Bophuthstswana as part of the government’s policy of establishing “African homelands” called Bantustans.

Between 1968 and 1975, under the harsh apartheid segregation laws, black people were relocated from black settlement areas in and around white proclaimed areas of Pretoria and dumped on the streets of the Winterveldt squatter settlement. Winterveldt became a sanctuary for homeless, unemployed blacks caught between rural landlessness and urban illegality. The area is typical of a rural community in a designated agricultural setting in South Africa although there is very little formal agricultural economic activity — primarily some animal herding or small-scale home gardens. Economically it is tied to the more urban economy near Pretoria. The residents of Winterveldt believed that they were

the lost and forgotten children of oppression

and the settlement was, at one time, known as the dark city.

Winterveldt was formally incorporated into the Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality in 2001. The City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality (also known as the City of Tshwane) is the metropolitan area that forms the local government of northern Gauteng Province. The Metropolitan area is centered on the city of Pretoria with surrounding towns and localities included in the local government area.

Winterveldt has many of the socio-political-economic challenges faced by people living in black townships. Initially seen as dormitories for an urban labor force, townships were allowed very little enterprise, industry, or businesses. Thus the main economic activity relied on the informal sector, such as small mom-and-pop consumer stores operated out of the home, back-yard auto repair shops, roadside stalls selling home-grown vegetables, outdoor barber and beauty shops — all of which exist today. Outside of the informal economy, there are virtually no employment opportunities for township residents. The unemployment rate is high, estimated at 70 percent. For those holding formal sector employment it means daily taking a train or local taxi into town (Pretoria) and spending about 30 percent of their income on transport.

Winterveldt lacked basic water and electrical infrastructure until the early 2000s when there was a major push to bring municipal water and electricity to homes. However this effort proved to be uneven across the community with some homes connecting to the grid (an increase from 31 percent to 81 percent connected) and 20 percent of the population remaining without electricity or illegally connected. Being connected to the grid does not guarantee a flow of electricity. South Africa is subjected to periods of rolling electricity blackouts called load-shedding when the state-power company cuts of the flow of electricity because of the inability to generate sufficient power to meet the country’s demand. While load-shedding affects the whole country, it disproportionately affects townships. Many homes are directly connected to the municipal potable water system; other residents live in communities with one standpipe serving 45 to 50 people. Sanitary facilities are predominantly pit latrines; although some residences have flush toilets.

Housing varies from multi-room adobe brick dwellings with either tin or tile roofs to one room tin shacks. A government housing development plan has provided approximately 12,500 adobe brick homes with electricity and running water, although a number of these stand empty because the government has not allocated them to residents. A significant number of Winterveldt inhabitants currently reside in dilapidated, decaying, and crumbling housing or in squatter communities of one-room tin shacks.